On the shelf

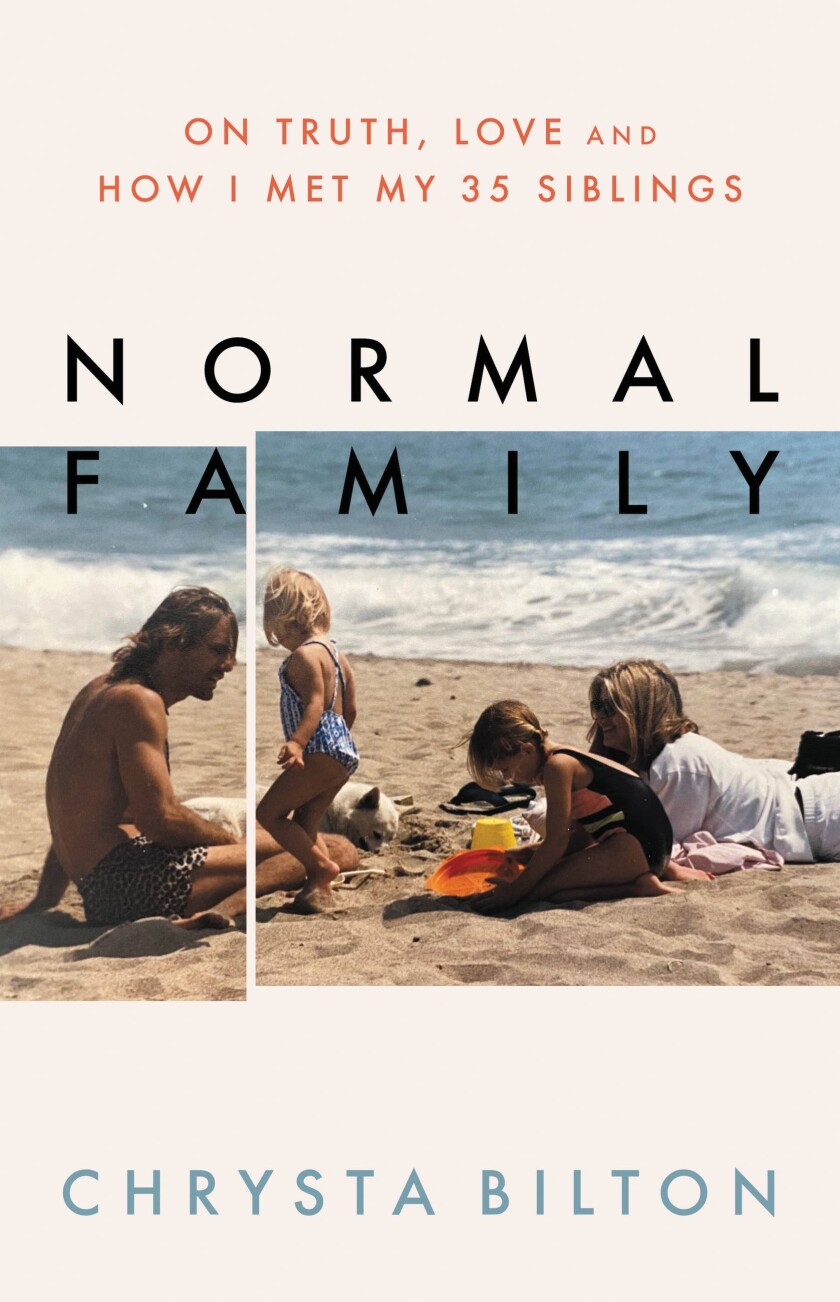

Normal Family: About truth, love and how I met my 35 siblings

By Chrysta Bilton

Little, Brown: 288 pages, $29

If you purchase books linked from our site, The Times may receive a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Chrysta Bilton’s memoir Normal Family has an ironic title. It also took a long time. Bilton, now 37, began writing about her unconventional clan when she was a teenager, but at the time she didn’t even know half of it.

Here’s what Bilton knew: Her mother, Debra, was an “incredibly original” character — she was friends with Warren Beatty and worked as presidential candidate Ross Perot’s “civil rights coordinator.” Most importantly, as a single gay woman, she had had two children, Chrysta and Kaitlyn, in the 1980s. She also had a penchant for Ponzi schemes and disliked many of the basics of parenting; Bouncing between relationships, she bounced the trio around Southern California while her addiction dragged her down.

Debra Bilton holds Chrysta in her arms on a beach in Los Angeles, California while father Jeffrey Harrison looks on, 1984.

(Courtesy of Chrysta Bilton)

The girls’ father, Jeffrey Harrison, refused to come to their aid. A sperm donor, he was in and out of her life. His parents were wealthy, but he’d skipped college to study Transcendental Meditation and he was floating aimlessly through life spouting increasingly wild conspiracy theories. A former Playgirl centerfold, he also battled addiction and depression.

While Debra was in rehab and the sisters camped out in an abandoned office, teenage Chrysta — also in a relationship with a volatile rich boy — began writing a screenplay about the instability surrounding her.

It was the first of many attempts over two decades to tell her story, which have always been shelved because ultimately she knew it was incomplete. “I had a lot of healing to do first,” she explained during a recent video call from her home in Los Angeles. “I didn’t have enough distance to have a healthy perspective — I had to work through a lot of grudges so the book wasn’t just filled with that. There was a lot of joy and happiness in our lives, as well as dysfunction.”

She also knew that she didn’t know the whole story. At first, her mother had “a precarious relationship with the truth.” Who knows if she really slept on the Sphinx in Egypt, marched with Angela Davis while at UCLA, or introduced Buddhism to Tina Turner? Debra had not fully explained her past or present. And then there was Bilton’s father, not so much an unreliable narrator as a narrative black hole.

Bilton’s perspective shifted dramatically after a 2007 New York Times article revealed that Harrison had also been an anonymous sperm donor to countless others — something Harrison had promised Bilton’s mother he would never do — and Bilton with one growing number of half-siblings.

Stunned, Bilton turned down efforts by newfound family members to bond. “I’ve had so many different types of families,” she says. “I didn’t want anything to do with one more sibling, let alone dozens. It gave me a huge panic attack.”

She wasn’t ready to share her life — not with new siblings, or with readers, not after leading a life of secrets. Bilton had spent her youth full of shame — having a lesbian mother and not a great father, hiding under a table while her landlord knocked and yelled to evict her.

“During college and even after, my closest friends didn’t know the truth about me,” she says. “It was a sad, lonely existence.”

Eventually Bilton sobered up – a process that tends to drive public accounting. She started telling friends about “little things,” but she didn’t really learn to open up until she met her husband, Nick Bilton. “He’s a journalist, so he asked a lot of questions and there was no way around them.”

Debra with Chrysta in 1985. According to Christa Bilton, her mother had “a precarious relationship with the truth.”

(Courtesy of Chrysta Bilton)

Then the dam began to break. “It was incredibly healing to tell someone my truth and be loved for it,” she says, choking a little. “I’ve just started to be more open, and people are so full of compassion when you’re honest with them. I think so many people can benefit from not being ashamed of the hard things they’ve been through.”

With a more open mind, she was able to see more of her half-siblings’ questions. One named Jennifer closely resembled Bilton’s sister, Kaitlyn; she had the same obscure gardening and philosophy books as Bilton; and there, on Facebook, was a picture of Jennifer in the same studio in Florence where Bilton had once painted. (Her old roommate was even in the photo.)

“She was so excited about this larger biological family and how wonderful it was,” Bilton recalls. “Instead of getting angry at this family, I could see the beauty in it. She really changed my perspective.”

Bilton now shares strong bonds with several half-siblings and often muses on their uncanny similarities (almost all love cats and philosophy) and the genetics that underlie her own life story. “It has expanded the understanding that some of my challenges are biological in nature, which has proven incredibly empowering.”

However, there was still a story to be written. She didn’t want to make it a simple memoir, instead wanting to interview family members and incorporate multiple viewpoints, particularly on incidents that preceded her birth or vivid memory. For the most part, her parents’ factual recollections matched “perfectly,” she notes. “It was just her feeling who was to blame would differ.”

She also learned a lot. Her father confessed that Debra paid him to keep showing up in Bilton’s life. “He just told me that factually.”

Chrysta, left, with sister Kaitlyn in Los Angeles. During puberty, girls had to fend for themselves.

(Courtesy of Chrysta Bilton)

It took some time to get over that — but the oral history approach enabled what Bilton had craved all these years: perspective. Debra didn’t know any other gay women raising children in an overtly homophobic society. “I can’t even believe what it must have been like for her,” says Bilton. “As crazy as it is that she gave a guy a $100 bill to come to my birthday, I kind of get it now.”

It wasn’t quite so easy for her mother. Debra, now sober for years (“and an incredible grandparent”), felt safe speaking openly about her past — including the drinking, violence, and suicide of her own childhood in Beverly Hills. That was partly because she had come to believe that this Bilton writing project would never see the light of day.

“She thought it would be just a good time with me and spent dozens of hours talking about her life,” says Bilton.

When Bilton gave her the finished book, the result was “a really big panic attack.” Not wanting to risk “a beautiful relationship,” Bilton considered shelving the project. “But we had several therapists involved and we worked through it and she’s proud of it now.”

Finally, Bilton has no unfinished business — and no regrets. “I was grateful to be able to learn everything,” she says. “You always benefit from knowing the truth.”