[ad_1]

Nonprofits are known for low wages, burnout, and high turnover. Some former employees said they expected disorganization or poor treatment from the SPD because these issues are common in nonprofit arts organizations, bookstores, and other creative industries. Former employees said the SPD executive committee, which also includes poets and publishers, was absent or unavailable when it came to working conditions at the SPD.

Cunningham said in a written statement that the working conditions and culture at the SPD are not significantly different or worse than at an underfunded non-profit organization. He said the main obstacle to any change is always a lack of resources, not a lack of will, and there is also a lack of consensus or articulation among staff about the real, practical changes they want to see.

“For many years, long before me, the SPD was a small group of poets who tried to bring out books,” says Jeffrey Lependorf, the SPD’s managing director until 2020. “We weren’t HR professionals. We did our best to learn and establish HR processes. We have done well in many ways and have often failed in our endeavors. I think that’s fair to say. “

Bernheimer said that since the allegations were first raised online in December, the SPD board had invited employees to board meetings and created a liaison process between staff and board to improve communication.

But although some of the longstanding problems of the SPD are common to many organizations, the SPD occupies a unique position as the only non-profit literature distributor in the country. Small literary publishers rooted in social justice and committed to delivering underrepresented voices to readers have few other means of dissemination.

“There is almost no other. Whoever there was, the SPD is the one that is left. As we speak, everything in the commercial distribution world is consolidating,” said Clay Banes, a former SPD employee. “So many writers, so many publishers, so many poets, for the most part none of these people want to fall for it. Nobody wants to harm the SPD, not even me.”

But the pandemic resulted in workers across the country questioning not only their safety, but also their appreciation at work – including in nonprofits and bookstores. Current and former black and transgender booksellers at Pegasus Books in Berkeley and Oakland have launched an anti-racist bookstore initiative to call for better treatment. Bookseller at Moe’s books in Berkeley and Santa Cruz Bookstore Voted to form unions earlier this year, a rare move for an independent bookstore.

“I think there’s still a perception that these professions are somehow special or have cultural capital,” said Amy Wilson, poet, organizer, and graduate student at the CUNY School of Labor and Urban Studies. “But what workers say is you can’t eat [or] can’t pay your rent with cultural capital. “

Occupational toxicity

Many of the former workers who spoke to KQED said they tried to fix the SPD’s culture and structure internally, but it didn’t seem to change enough. The environment had become more and more hostile in 2019, they said when employees were told that the SPD was in the middle of a financial crisis.

“The SPD provides books that don’t bring much money,” said Jeffrey Lependorf, the SPD chairman at the time. “And the book industry was facing difficult times back then. And we were part of them.”

Employees said workers who vocalized about changes in the SPD seem to be the most scrutinized during the SPD’s financial challenges.

“It is as if the SPD could break up at any moment, [so] we have to be hypervigilant and never change our way of working, “said E. Conner, who worked for the SPD during this time.

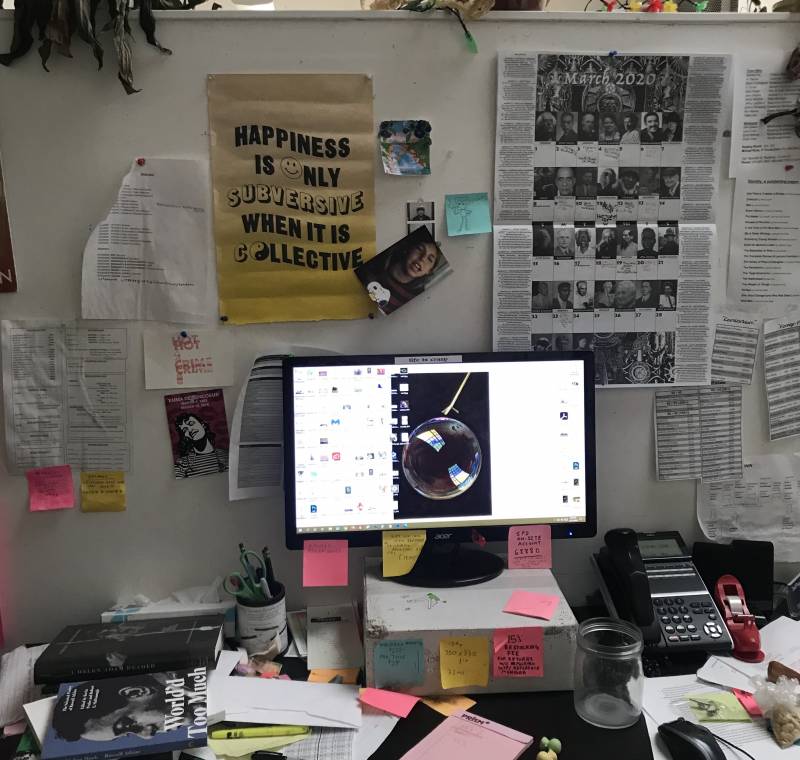

Former employees said managers conducted an “efficiency audit” to identify layoffs. As part of this effort, staff said they were asked to describe in detail what they were doing during the day. But Conner said it felt like the manager didn’t believe her even when she explained how she spent her work day.

“When I explained what I did, I was told, ‘But you don’t really do that, do you?'” Conner said. “And I explained that, ‘I’m just trying to tell you what I’m doing.’ Everyone was afraid that we would lose our jobs. “

Another former SPD employee, Nich Malone, said he was open to some issues at the SPD, such as the lack of clear job descriptions or the need for professional boundaries. But he said his suggestions only seemed uncomfortable to some of his bosses, and the efficiency test felt like an attempt to wear him down.

“It was literally sitting in a room for an hour, not working, so you could justify your job,” said Malone. “It would kind of break you down to work harder, to keep your job.”

During these audits, Lependorf lived on the other side of the country – another problem that employees found frustrating as they and their lower-paid colleagues faced layoffs. “He lived and worked in Hudson, New York while Small Press Distribution is based in Berkeley, California,” Conner said do it well. “

Lependorf said the remote position would make sense for years, considering that there are many valuable connections in the New York publishing industry. However, he said his distance from the nonprofit seems less practical as the climate in the workplace becomes more toxic.

“There were problems with gender identity, there were problems with gender bias, there were problems with crossing boundaries and [it] got more difficult … it was certainly difficult for me not to be there, “he said.” I was able to be a little helpless.

He said management was working hard to make sure employees could keep their jobs, but he could also understand how employees felt threatened by the financial troubles.

“We were really, really trying to listen. We were out there trying to make pennies to keep everyone busy,” he said. “You don’t want to scare your employees, but you don’t want to hide anything from them either. It’s a difficult balance.”

Lependorf left the SPD last year, and Cunningham said Lependorf’s departure was the solution to the financial challenges. (Lependorf said he was planning to leave in a year or two anyway.) Cunningham, who became managing director after Lependorf left, said he couldn’t comment on personnel matters because of privacy concerns. Cunningham said of himself that he had treated all employees fairly and equally and that in his role as SPD leader he had not seen another SPD director treat an employee in a way that he considered unfair, unequal or considered Retaliation.

Around the time the nonprofit was facing financial problems, management learned about errors related to payroll. The SPD leadership said in a statement last year that a total of five employees were underpaid, and that the employees had not received legally compliant pay slips; they showed neither hourly wages nor hours worked.

One person was underpaid by more than $ 4,000 in total for most of 2019, documents with KQED show.

The SPD board member Cunningham and the SPD finance director Andrew Pai published a statement in which it said that as soon as the executives became aware of the errors in the payroll, apologized to the employees, informed all employees of the error and the Fixed bugs – including paying missing wages with interest to those affected. They said they also switched to another payroll company that complies with the applicable regulations.

Former employee Malone said these financial problems and mismanagement contributed to the hostile environment at the SPD in which employees felt they had to justify their position and it eventually became too much. Malone decided to leave last March.

“I just figured if I could leave the organization it would at least mean my friend, who’s also on the chopping block, is unlikely to lose his job,” he said. “I couldn’t still be part of something I loved so much and watch it slowly die.”

More than 60% of the employees who worked for the SPD in September 2019 have since left the non-profit organization.

[ad_2]