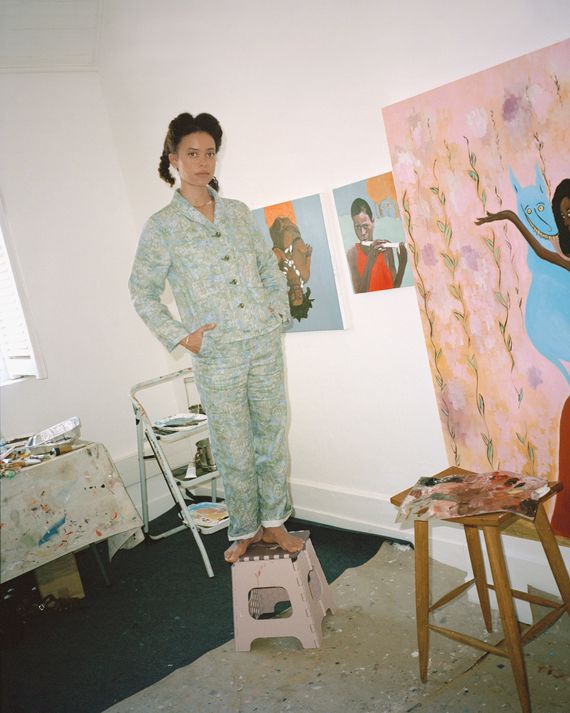

Cassi Namoda.

Photo: Alina Asmus

“Some would say that in your late 20s you’re a bit late to start a career as a painter these days, which is strange and unfortunate,” says Mozambique-born artist Cassi Namoda, 33. After studying cinematography at the Academy of Art University in San Francisco and worked for fashion designer Maryam Nassir Zadeh, who sourced crafts from abroad to sell in the shop – Namoda turned to painting from a very personal place. She lived in Los Angeles and longed for her home. “There is a term in Portuguese saudade, it’s a longing that can’t be replaced,” she says. A self-taught artist, she began showing paintings in a friend’s living room, then in another friend’s bookstore, and built her career through word of mouth. Now she is represented by the Goodman Gallery and François Ghebaly.

Namoda last painted in Cape Town, South Africa for an exhibition this summer. “My choice to be physically here is that I’m saying I want to connect with people,” she says. “I don’t want to just send pictures and say, ‘Okay, sell them.'” Later this year she will be spending some time in Guatemala City working on an exhibition of ceramics, drawing, performance and video art in an open floor plan for the experimental gallery Proyectos Ultravioleta. Her way of traveling and painting from new places is intentional, a way of slowing things down in an industry that can otherwise become “very commercial very quickly.”

Namoda spoke to The Cut about her artistic journey, her inspirations and why the light in East Hampton, where she lives, is different than anywhere else.

What got you on the path to becoming a painter in your early life?

It was my nature viewing time in Kenya, where I lived when I was about 6 years old. I was so in love with these animals that I really wanted to have pictures of them in my room. I used to draw them obsessively whenever we came back from a safari and it stuck with me. I drew continuously through middle school.

I moved to LA when I was 25, and the geography of Los Angeles felt very strange to me. So painting became the form in which I decided to negotiate my homesickness. I was surprised because I have a natural tendency to be a writer. Painting was something I always did growing up, but school interrupted that path for me to find other forms of expression.

I’ve just started drawing again. It feels very vulnerable; It’s like writing to me. My next exhibition, entitled “Tropical Depression” at Xavier Hufkens in Brussels, consists essentially of large drawings with a minimal amount of paint.

You said you started painting because you were homesick. As someone who was born in Mozambique and has lived in Indonesia, Kenya, Benin and Haiti, what does “home” mean to you?

I call Mozambique home even though it is not my home. It is my ancestral heart. My mother is there, my family is there, my grandparents are there in the ground. We moved quite a lot when we were growing up. My father had different ideas about life and experiences and about seeing the world. My practice also benefits from this. If I look at the work of Emil Nolde, or even Gauguin or van Gogh, these painters would travel and they would exist in these places. In a way, these paradises, these foreign lands, became exotic. But I don’t exoticize; I exist in a black body. I’ve lived in many places. I understand the world in a way that goes beyond a textbook, but more through the nuances. So I feel like I can be anywhere – Budapest or Tangier or Kyoto – and I’m very excited about a kind of familiarity in the sense of a new experience. We need something new in our human experience. But then I have to withdraw and remain seated at everything. I think East Hampton is that place for me right now.

What excites you about the painting profession?

It’s almost like you’re always negotiating with yourself. At the end of the day you have to sit with yourself and ask yourself: is that really me If that can be answered, then I know I did something honest, authentic. At the end of the day, when I’m not painting, I feel kind of incomplete.

Photo: Alina Asmus

When you first started painting in LA, how did you nourish yourself with your art?

When I started I was really shocked that all my friends wanted the pictures. It was such an amazing thing. All I really needed to do was sell a painting or two a month and that would help. Also remember that my work on paper sold for $500 to $1,000 – my watercolors and paper didn’t even cost a fraction of that. My materials weren’t really the issue, and I didn’t need a studio. Only much later, when I was painting on canvas and had more curious people, I thought: Okay, I guess I need to have studio visits, not my ex’s garage. And I have a small studio.

Now painting supports my lifestyle but at the same time I don’t want to over produce. It’s a purely logistical business method of approaching the work. You can’t flood the market. The painting must have some kind of preciousness. It’s also very physical. I don’t have an assistant, so collaborating on projects with brands like J.Crew helps. Whether it’s the perfume I designed with Linda Sivrican or my collection with J.Crew – although the perfume project was entirely based on charity – I’m curious to create nuances in the collaboration that still retain the spirit of the art can have.

You recently worked on a textile for Marimekko and started a jewelry collaboration with Catbird last summer. How do you combine your interests in other areas with your painting?

I need my brain to work in different ways. Everything informs something else. Now I’m taking ballet, so that informs something about my practice, about me as a person. It makes your feet so strong that now I can’t paint with shoes on. My feet are like No, I have this. i have the floor. As soon as I come back to the studio refreshed after learning something new, my mind works differently.

How does living and working in New York or your home base in East Hampton influence your art?

So I came up with a pretty nice situation. I like the history of artists who came before me. Jackson Pollock’s Studio is less than five minutes from mine. Just knowing that it exists there as a pillar is really cool. When I think of Helen Frankenthaler – there’s something that almost gives me more energy.

The colors also inform me. There is something very special about the light there. It feels like a chunk of land has just drifted away into a gentle morning sunrise, and it kind of stays that way. And my relationship with the sunset was very important to me. Pausing my studio practice, rushing to the ocean to watch the sunset, and retreating back to work – it’s almost as if time moves in a very circular motion for me there, which I find very ancient. It’s a good retreat. I don’t have many distractions there. And if I have to go into town at 8am and eat at Balthazar and then jump in and see some shows, see some friends, that has its place too. We need to keep recharging and seeing other people.

As you mentioned earlier, you use color in your work. What is your approach to the vibrant hues you use?

At some point I would like to make my own pigments. I think that’s where it’s going. When it comes to painting, I usually just stare at sketches, sometimes for a month, before even deciding what colors to embody in the work. Then I start living and breathing those colors, and it just shows in a lot of different ways.

When I did the Mendes Wood exhibition in São Paulo, it was this really bright fuchsia with this opaque black and this powder blue. It was a very narrow show. I have worked against a background of sorrow and sorrow because it has been a very difficult time in Brazil and around the world with COVID. The fuchsia symbolizes compassion.

I also think about color in the realm of spirituality. Every religious philosophy or theology has colors that embody it. In Hinduism, marigold is really powerful. The Catholic Church also has its specific colors. I think color is probably a religious approach to painting.

Do you feel that your presence in the art world and your growth serve some kind of social duty?

One hundred percent. This is exactly what happens with any kind of work framework once a certain status is given. I like connecting and showing people. When I presented my first show at Nina Johnson in Miami in 2018, I invited the local postman and the woman who braided my hair and they just came and looked and they were just so amazed by the size.

Just yesterday a girl from the café next door said: “What are you doing? You’re always covered in paint.” I said, “I’m a painter.” And she says, “What?” She’s from Zimbabwe. And I said, “Why don’t you come over?” She came at the end of the day and just said, “Wow, you do that? I didn’t know we could do that. I didn’t know black women could do that.” That’s why I say accessibility. Because these ideas are not often introduced on this continent. When I can be around to just chat with people in a very democratic way, that feels good to me.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.